A Deep Dive into ‘All the Light We Cannot See’: Critics’ Perspectives

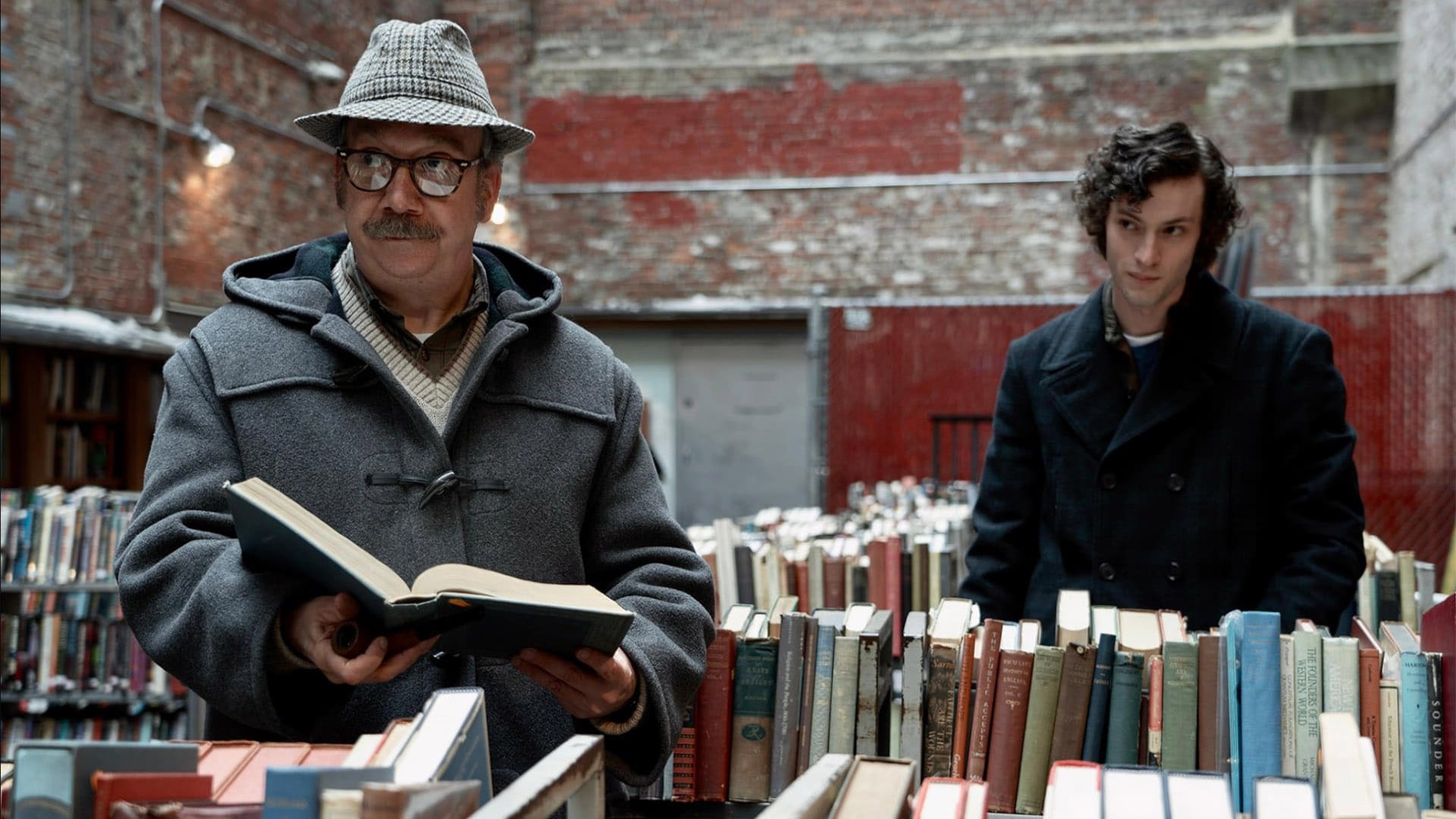

Shawn Levy’s Epic Series ‘All the Light We Cannot See‘ premiered on Netflix on Nov. 2, 2023. Based on Anthony Doerr’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, the four-episode limited series unfolds in a besieged city, immersing viewers in the lives of Marie-Laure, a blind French teenager, and Werner, a German soldier. Their paths cross in occupied France as they navigate the challenges of World War II.

While the series has a bright cast, its potential is often snuffed out by a tonally awkward blend of serious and silly. The television adaptation falls flat in comparison to its original source material. Critics note that it may not be a typical comfort watch, yet it offers a glimpse into a simpler time, contrasting with its wartime setting.

- The casting of visually impaired actors, such as Loberti and Nell Sutton, who portrays young Marie, adds authenticity to the characters, enhancing representation and genuine portrayal of the story’s protagonists.

- However, great actors and good source material are not enough when they’re in the hands of the wrong filmmakers. Nothing about this final product suggests that Levy or Knight was the right choice to bring this story to the screen.

Critics argue that whatever was transcendent or lyrical about Anthony Doerr’s novel gets lost in translation from page to screen in this hackneyed and surface-level adaptation from screenwriter Steven Knight and director Shawn Levy. Insight into the human condition is traded away in favor of underdeveloped characters who speak in on-the-nose metaphors.

Moreover, Levy’s directorial choices leave much to be desired. Marie-Laure is often filmed with precious close-ups that present her as an object of pure goodness, but she is given little to no moments that show her depth of character. Each actor feels like they’re playing a character rather than something resembling real life.

Part of the fault lies in Knight’s script, laden with clunky exposition or overly flowery language. The dialogue becomes increasingly worse, losing all nuance and thought, leading to a drearily slow yet stupidly rushed experience.

Critically, the acting is almost uniformly bad, and the accents are particularly concerning to some. Despite this, the emphasis on storytelling is what critics have found to be pretty terrible overall. The adaptation appears muddled and flat, leading many to say it will disappoint viewers who hold the original novel in high regard.

Notably, not only are the characters Doerr creates beautiful and wholesome, but the intricate plot-line and well-developed metaphors create the enchanting World War II story that is ‘All the Light We Cannot See.’

Is the Mini-Series Adaptation Faithful to the Book?

Director Shawn Levy consulted Anthony Doerr for historical accuracy in the adaptation of All the Light We Cannot See. Levy stated that Doerr ‘wasn’t precious’ about his adaptation but wanted to ‘get the history right.’ This collaboration allowed the series to portray significant events accurately, such as the invasion of Paris and the exodus of millions from their hometown.

The television adaptation introduces new characters, such as Nazi soldiers Captain Mueller and Schmidt, to highlight the threat of war and the growing tension during World War II. Levy aimed to manifest the evil of the Nazi party through these characters, a creative decision that Doerr found effective.

However, significant changes were made to character relationships. For example, between Madame Manec and Etienne, in the series, they are depicted as siblings. Madame Manec dies of pneumonia, inspiring Etienne’s advocacy work in the French resistance. This contrasts with the novel, where she has a different fate and Etienne survives the war, reuniting with Marie-Laure.

Moreover, the ending of the series diverges significantly from the novel. In the show, Marie-Laure kills Reinhold after Werner attempts to protect her, whereas in the book, Werner kills Reinhold before he can reach Marie-Laure. The series offers a more hopeful conclusion, with Marie-Laure throwing the Sea of Flames into the ocean, while the book ends with a more somber reflection on Werner’s fate.

Despite these elements, critics have acknowledged the adaptation’s shortcomings. One review noted that, in translating the hefty book to TV, Netflix is clearly hoping to gain some of that sweet critical clout for itself. However, it is unlikely, as the adaptation is described as mostly mediocre, occasionally veering into outright bad.

Furthermore, with Shawn Levy on directorial duties and Peaky Blinders writer Steven Knight dealing with the screenplay, any subtleties or quietness are stamped out in favor of belching out all of the subtext as pure text. The characters are constantly talking about what they’re doing and how they’re feeling.

The ultimate effect of this approach is to turn Nazi-occupied France and the slaughter of millions into a cutesy playground for Instagram post levels of inspiration. Critics have questioned whether the book was simply too weighty for Levy and Knight to dissect or if they believed that viewers would be bored if the story took a breath and stopped for longer than a minute.

Overall, All the Light We Cannot See is described as half-baked, leaving behind scraps of potential but largely a hash of two-dimensional figures stuck in an interminable slog. Perhaps fans of the book will be satisfied to see the characters they love in the flesh, but many cannot imagine anyone being truly thrilled with something so blatantly made by people who didn’t know nor care to try harder with what they had.

Lastly, in addition to the deviation in character fates, the show kills off Etienne rather than having him end up in prison and ultimately reunite with Marie-Laure like in the book. Moreover, many reviews bashed the show, bemoaning the fact that it ‘changed the ending.’ Notably, Netflix’s adaptation brings new characters and a larger cast to the story, adding depth to the primary characters.

All the Light We Cannot See: A Review of the Cinematic Experience

Overview

“All the Light We Cannot See” is not, in the strictest sense, a comfort watch.

Like the Pulitzer Prize-winning Anthony Doerr novel on which it’s based, the four-episode limited series takes place in a walled city under siege by a bombing campaign. Its trapped civilians are unable to evacuate — hardly a relaxing break from today’s headlines.

Adaptation and Storytelling

As adapted by screenwriter Steven Knight (“Peaky Blinders”) and director Shawn Levy (“Stranger Things,” “Free Guy”), the series leans into sentiment and moral simplicity.

Knight and Levy aim for an uplifting, inspirational tale of connection that transcends division, distance, and prejudice. However, they instead deliver a flat, jumbled story that lacks the desired effect.

There’s a romantic tone to this story that borders on fairy tale-like fantasy.

Marie is locked in an attic á la Rapunzel, while a wicked jeweler-turned-Gestapo-officer (Lars Eidinger) is on the hunt for a magical gem.

Thematic Elements

A more substantial change is in how “All the Light We Cannot See” depicts, or doesn’t, the nuance of growing up in a fascist state.

The symbolism of Marie’s condition is straightforward and left largely intact from the book. She’s both part of a population threatened by Nazi ideas of genetic purity and in tune with deeper truths than skin-deep appearance.

Ultimately, ‘All the Light We Cannot See’ suggests that, despite the profound challenges of life, there is light to be found in the unlikeliest of places and moments.

One of the key points of ‘All the Light We Cannot See’ is that war is futile and impersonal. War brings out the horrific side of humanity.

Character Development and Casting

The Netflix adaptation has a few changes that improve upon the book.

While reading the book, you have trouble depicting the experiences of Etienne, Werner, and Marie. In the adaptation, Levy incorporates flashbacks from the present to before the war started. These flashbacks are so well done, emphasizing the pain each character must feel. The storyline for the Netflix adaptation is a 10/10.

Aria and Nell, both blind in real life, made a significant impact with their casting. This provided a perspective nobody had ever seen before and represented a new step for blind actresses. For Werner, Shawn found Louis Hofmann, a German actor, fitting the book well. The other characters are also well done. Who knew that Von Rumpel, the antagonist of the book, could be so deadly? For casting, I would give it a 10/10.

Accuracy and Cinematography

I would give the adaptation a 9.5/10 for book accuracy.

One change I appreciated was the development of Madame Manec and Étienne. Originally in the book, Étienne wasn’t part of the Resistance after his WWI experiences. In the adaptation, he is portrayed as the leader of the Resistance, and Madame Manec was only the housemaid to Étienne. I love how they made Étienne and Manec siblings because it enhanced the relationship hinted at in the book.

The cinematography was spot on. From the accurate depiction of Saint Malo to the bombings, it was beautiful. The audience is drawn into the events of the adaptation. I also like how, during time jumps, they add the date and location, which helps differentiate between Marie’s and Werner’s plots.

Exploring Characters: Who Shines in ‘All the Light We Cannot See’?

Character Analysis in ‘All the Light We Cannot See’

Marie-Laure LeBlanc

Marie-Laure LeBlanc is a blind French girl and one of the novel’s protagonists. She is sheltered but also brave, self-reliant, and resourceful.

Marie-Laure grew up during a challenging time in history. She experienced personal tragedies, but she never loses a sense of wonder in the world around her.

She became blind at the age of six but learns to adapt to this new reality. Marie-Laure is inquisitive and intellectually adventurous. Her father is a driving force in her new life, encouraging her to not let the loss of sight destroy her life.

He builds her a scale model of the area of Paris near their home, making her lead him home from work every day. Shortly after it becomes apparent that Paris will be overrun by the German army, Marie and her father flee the city.

They carry with them the Sea of Flames as they travel to the city of Saint Malo, where Marie’s great uncle, Etienne, lives. The war progresses, and Saint Malo becomes occupied by the Germans. During this time, Marie loses her father because the Germans accuse him of being a rebel.

Eventually, Etienne’s maid, Madame Manec, takes over as her primary caregiver until she dies. With no one else left to care for her, Etienne steps up and begins to watch over her.

As the war nears its end, Marie learns that her father has left her the Sea of Flames. She faces harassment from Sergeant Major Von Rumpel, who is searching for the diamond. When the German siege begins, Marie must hide in the attic to avoid being attacked. Using her uncle’s radio, she calls for help.

Werner Pfenning comes to her rescue after hearing her pleas over the radio. Doerr depicts Marie-Laure as a quiet and observant young girl.

Werner Pfennig

Werner Pfennig is a young, intelligent German boy with whitish-blond hair and blue eyes. He grows into a kindhearted and intelligent young man, highly motivated to learn.

Initially, his scope of experience is limited as he grows up as an impoverished orphan in the poor coal mining district of Germany, raised in an orphanage with his sister, Jutta, by Frau Elena.

However, his horizons change dramatically when he finds and repairs an old, broken radio in an alley near the orphanage. Werner falls in love with this radio and the physics of broadcasting. With time, he becomes more engrossed in physics and radios.

After a series of brutal examinations, he is chosen to attend a highly selective school in Schulpforta, where he excels in his studies. He is selected by his professor, Dr. Hauptmann, to help create a radio tracking device for the German army.

At the school, Werner meets his only two friends: Frederick, his bunk mate, and Frank Volkheimer, an incredibly large schoolboy known as ‘The Giant.’ However, 16-year-old Werner is soon sent to the Eastern front to fight in the war, serving under Volkheimer’s command to track down rebel radio communication.

As he travels across Europe, his duties lead him to Saint Malo, France, where he meets Marie-Laure. Throughout much of the novel, Doerr portrays Werner as a young, innocent boy, despite fighting in the war.

He often feels regret after finding rebel radio operators, as he feels responsible for their deaths. A haunting memory from the war is the killing of a young Romanian girl—an image that will distract him for the remainder of his time in service.

Daniel LeBlanc

Daniel LeBlanc, Marie-Laure’s father, is selflessly devoted to his daughter. He spends long hours teaching her Braille and crafting elaborate models of Paris and later Saint-Malo to help her navigate her environment, showcasing a deep bond between father and daughter.

Frank Volkheimer

Frank Volkheimer is described as a huge, intimidating, and morally ambiguous staff sergeant who works as an assistant at Werner’s school. Initially, he comes across as a simple-minded, brutish thug.

However, when alone with Werner in the laboratory, a deeper side of Volkheimer emerges; he listens to and dances to classical music by Mozart, Bach, and Vivaldi.

Later, as Werner is sent to the Eastern front, he serves under Volkheimer’s command, who appears to protect Werner like an older brother would.

Jutta Pfennig

Jutta Pfennig is Werner’s younger sister. She is left behind when Werner departs for Schulpforta, resulting in feelings of abandonment and resentment towards her brother. During the war, they maintain contact through letters. After the war, Jutta returns the puzzle box that Werner retrieved to Marie-Laure.

Sergeant Major Reinhold von Rumpel

Reinhold Von Rumpel is a sergeant major in the German army responsible for evaluating art, jewelry, and gems. Diagnosed with cancer during the novel, he zealously searches for the Sea of Flames—a gem believed to protect its possessor from death but curses those close to them.

Why Are Critics Divided Over ‘All the Light We Cannot See’?

The series, which is broken into four episodes, looked promising upon its release. It is directed by Canadian Shawn Adam Levy, known for the Night at the Museum film franchise. A through line between All the Light and Museum is that many scenes within All the Light were set at the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle (The National Museum of Natural History). However, unlike The Night at the Museum, the series takes place during World War II, amidst the destruction of war-torn Paris.

Critics’ Scores:

- All The Light We Cannot See (2023) has a 28% critic score on Rotten Tomatoes.

- The audience score is 82% and IMDb ranks it at 7.6/10.

General Criticism:

Critics have so far branded the latest offering from Stranger Things executive producer Levy and Peaky Blinders writer Steven Knight a shonky, star-studded dud, a trite, turgid mess and quite simply terrible.

- The Guardian described it as terrible with almost uniformly bad acting and dialogue that gets worse, feeling drearily slow and stupidly rushed.

- Early reviews have branded it a ‘shonky, star-studded dud’, a ‘turgid mess’ and simply ‘terrible’. Ouch. It’s the much-hyped Netflix series from director Shawn Levy. But now the initial reviews are in for All The Light We Cannot See – and we’re sorry to say that they are not good.

- Here’s a selection of what critics have said about All The Light We Cannot See so far: ‘It is terrible. The acting is almost uniformly bad. The dialogue gets worse and worse (or if it’s Von Rumpel’s, vurse and vurse). All nuance is lost, all thought has been excised and it feels both drearily slow and stupidly rushed.’

Character Portrayals and Writing Issues:

All the Light We Cannot See (2023) had the opportunity to present its storyline in a more truthful manner by incorporating German and French speaking actors to play the characters. Unfortunately, an all-American cast was selected instead. This choice made the film feel less realistic and removed from the World War II period it is supposedly set in.

When reading the novel alongside the series, it became clear that switching between the lives of Marie-Laure and Werner was a difficult task. The novel alternates their stories with every chapter, providing small snapshots. I think this is the reason the novel did not translate well into a screen adaptation. The series wanted to cover the experiences of both characters in-depth, but they should have picked either Marie-Laure or Werner to be the focus, rather than battling over finding ways to equally share their screentime.

Moreover, the series felt rushed. Although it was thought that packing an entire novel into four individual episodes would allow for more detail, Marie-Laure and Werner’s relationship progresses too fast. They meet in the final episode and almost instantly share a kiss. Marie-Laure is overly trustworthy of Werner and believes he is there to save her, even though she has never spoken to him in her life.

Notable Performances and Visuals:

Despite some positive notes, including a radiant lead performance from newcomer Aria Mia Loberti and a nicely shot visual style, critics noted that the series diverges significantly from the original book. Changes made the material louder, clumsier, and less emotionally rich.

Radio Times expressed disappointment with the overall quality of writing. While the series is visually impressive, it lacks convincing character arcs. There was a sense of missed opportunity with talented actors like Laurie and Loberti, as the writing did not allow their performances to shine fully.

Adaptation Concerns:

The Independent noted that while the casting of visually impaired actors was a good decision, Mark Ruffalo’s performance was criticized for lacking any French authenticity. The central chemistry between Marie and Werner was deemed incoherent due to the achronological telling, resulting in a cartoonish portrayal of a Nazi that does not honor the scale of suffering in history.

The Telegraph argued that the adaptation has clumsily scissored the source material to make it less dark and more optimistic, resultant in a preachy, sanitized, and sentimental portrayal. Characters were drawn in rudimentary strokes, with heroes depicted as saintly and villains as cartoonishly evil, failing to capture the complex humanity of the characters.

Ultimately, whatever was transcendent or lyrical about Anthony Doerr’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel gets lost in translation from page to screen in this hackneyed and surface-level adaptation from screenwriter Steven Knight and director Shawn Levy.

Should You Watch ‘All the Light We Cannot See’? A Viewer’s Guide

ALL THE LIGHT WE CANNOT SEE is a riveting and well-stocked miniseries filled with intense jeopardy. Each episode ends with a cliffhanger, keeping viewers on the edge of their seats.

The four-part limited series tells the story of a blind French girl named Marie-Laure and her father, Daniel LeBlanc. They flee the National Socialist Germans occupying Paris with a famous diamond that supposedly grants eternal life, but also brings harm to the owner’s loved ones. Daniel is determined to protect the diamond, as it belongs to France.

The two major narratives intersect as Daniel and Marie seek refuge in the coastal town of Saint Malo. They move in with a reclusive uncle, Etienne, who sends radio broadcasts for the Resistance, and an aunt who organizes old ladies as spies. Concurrently, the other storyline follows a young orphan, Werner Pfennig, a genius taken into Hitler’s radio squad to locate signals from the Resistance.

The show has been handsomely produced with a substantial budget. The dialogue, acting, sets, costumes, and direction are remarkable. However, some flashbacks can be disorienting. Moreover, the series has very intense violence, including torture and the killing of Daniel, despite minimal bloodshed. Notably, the Germans use the ‘f’ word several times, which seems out of place given its lesser impact in German language culture.

Despite its strong visual elements, ‘All the Light We Cannot See’ has received criticism for being a hollow adaptation of rich source material. The adaptation fails to capture the depth and subtleties of the Pulitzer Prize-winning novel it is based on.

Screenwriter Steven Knight, known for ‘Peaky Blinders’, has been blamed for turning Anthony Doerr’s lyrical narrative into cliches. Director Shawn Levy, recognized for the ‘Night at the Museum’ franchise, has been criticized for eliciting lackluster performances from talented actors like Mark Ruffalo and Hugh Laurie. Additionally, the score by James Newton Howard tends to dictate audience emotions rather than allow them to experience the story organically.

Conclusion

While ALL THE LIGHT WE CANNOT SEE is described as an extremely exciting and morally affirming miniseries that testifies to good triumphing over evil, it ultimately falls short. With strong Christian references but also notable coarse language and violence, it leaves many viewers feeling a sense of disappointment.

In conclusion, the series may hold worth for some, especially with the radiant performance from newcomer Aria Mia Loberti as Marie-Laure. However, many audiences and the spirit of the source material deserve better.